Alina Pinsky is pleased to announce the opening of her first Paris space. The inaugural exhibition 'Searching Eye' invites viewers to discover a selection of artists represented by the gallery. From magic realism to op art and abstract expressionism, it offers a broad panorama of artistic approaches spanning several decades.

Artists

September 2025

Pavel Gerasimenko

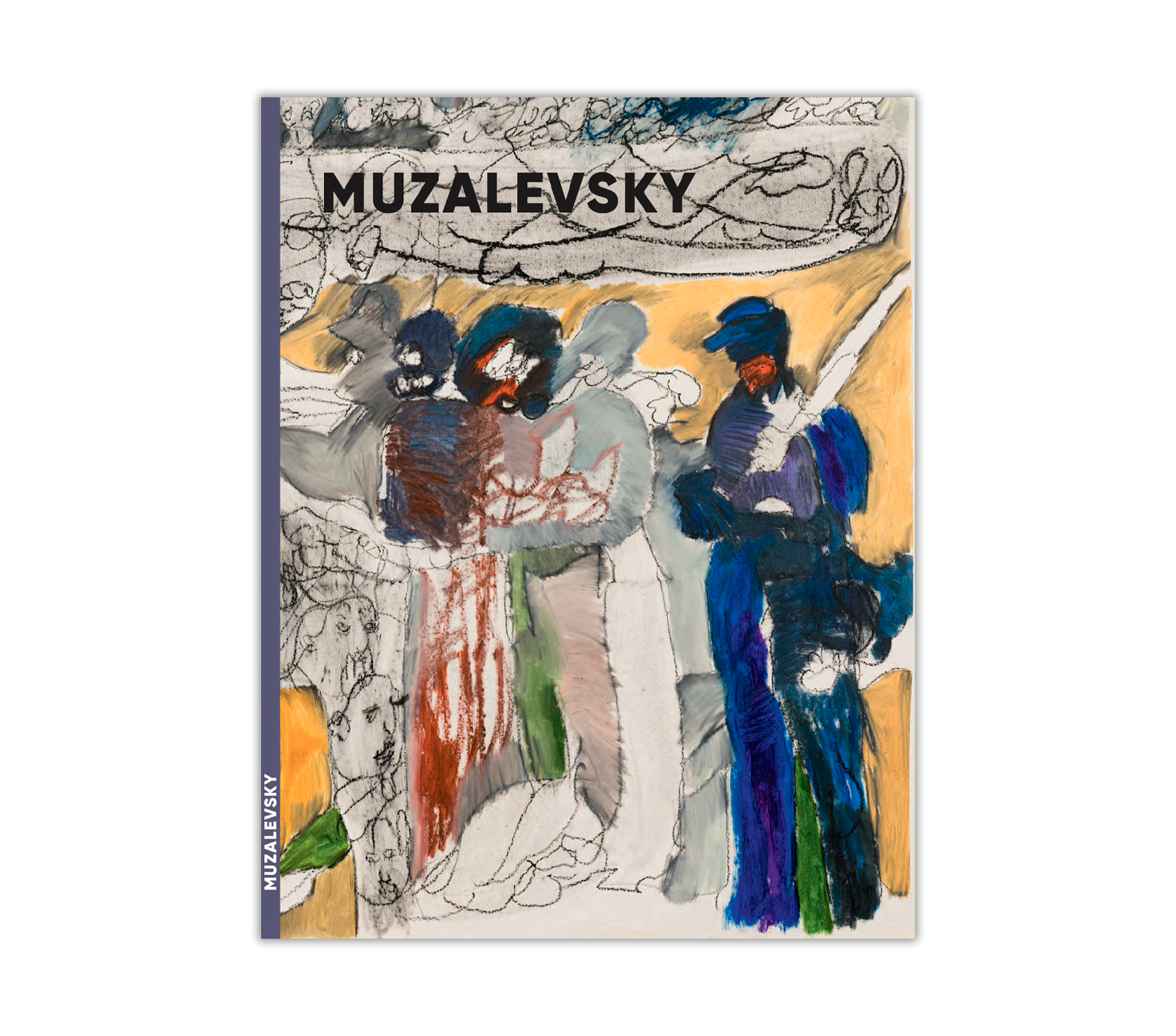

Among the traits that distinguish Evgeny Muzalevsky against the diverse backdrop of his artistic peers is his constant, fervent dedication to drawing. The 22 large-scale works comprising his new painting series were created in just under three months at the beginning of 2025. As often happens in childhood, drawing allows a person to construct a refuge — one that grows stronger with every line and can transform into a secret repository of the most powerful and precious impressions, thoughts, and emotions. Muzalevsky describes the emergence of these new works with the words: "I simply began pulling out things that matter to me from memory". Yet his art cannot be reduced to conventional psychoanalytic interpretation, even if the shifts in his painting serve as a reliable marker of personal transformation — to change his painting, in this case, means to change himself.

He enrolled at the University of Art and Design in Offenbach in 2020, not yet speaking German and, quite literally, possessing only one language — the language of painting. Since then, Muzalevsky has refined not only his linguistic skills but also his nomadic experience, becoming, like many, a "citizen of the world": the artist lives and works near Frankfurt, then in Moscow, then Barcelona, then Amsterdam, then in the Samara region, where he was born. In recent years, any travel has become fraught with obstacles: since the pandemic and lockdowns, movement has been increasingly tied to control and security. What was once a European achievement — the absence of borders — has been replaced by customs checkpoints and police inspections. Educational institutions impose their own boundaries on the artist, but unlike state borders, he can traverse them freely, carrying with him the material of art — which, for a follower of the Surrealists, becomes the dreams themselves. Muzalevsky emphasizes that he lacks formal academic training, and from this position, he continually questions and reevaluates his own skills. As such a "barbarian," he has never constrained himself in means or ends, yet his studies prompted a critical reconsideration of painting. He faced the necessity of reconstructing space to convey the sensation of contemporaneity.

In his new series, Muzalevsky remains engaged, as he puts it, in "capturing states and living through events," though this time, figurative depictions take on a more prominent role. After the crystalline precision of the black-and-white works from 2022-23 in his previous project "Monochrome, with Mom Behind Me," the artist does not merely return to chromatic and formal liberation — now, color envelops and presses against charcoal lines, while the marginalized graphic elements serve as narrative commentary on the shifting masses of color characteristic of his painting. With the reintroduction of color, alongside other techniques, his painterly motor skills transform: Muzalevsky rediscovers confirmation of his identity as a painter, which brings him palpable satisfaction.

Muzalevsky’s painting, like street vernacular, absorbs everything around it—music playing in the studio, old American comics, Japanese shunga prints, archaic tattooed ornaments, and the classics of world art. Diverse visual traditions layer upon one another; he engages with them through the urgency of plastic exploration and an immediacy more characteristic of modernism’s nascent era. Muzalevsky possesses an almost adolescent visual voracity—a quality once termed "everythingism" (vsyëchestvo) by the Russian Futurists.

His painting unexpectedly revives debates about the linguistic nature of abstraction, even though it seemed all "questions of linguistics" in contemporary art had been settled back in the 1970s, during conceptualism’s dominance. For the artist, whether his works belong to the figurative or abstract tradition is irrelevant. Just as "Bataille is not interested in 'form' or 'content,' but in the operation that displaces both," as Yve-Alain Bois notes in Formless: A User’s Guide, co-authored with Rosalind Krauss¹.

The space Evgeny Muzalevsky reveals has no visible or defined boundaries. Like few others — perhaps only a couple of names in contemporary Russian art — he possesses an ability for renewal and regeneration, growing new sensory organs, acquiring skills, and altering habits. For Muzalevsky, the most crucial thing is artistic articulation — the ability to communicate with the world and be understood. Painting can express what is most essential beyond words and meanings, and it is the only medium he really trusts.

---

¹ Yve-Alain Bois, The Use Value of "Formless," in: Krauss, R., Bois, Y.-A. Formless: A User’s Guide. New York: Zone Books, 1997, 304 pp.—p. 15.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

"How Do We Create Our Own Beauty?" The opening of the most "female" exhibition took place in Moscow.

.